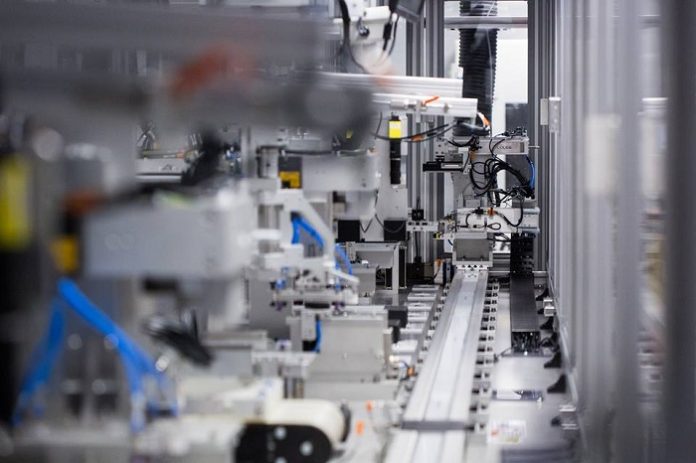

It did not participate in the government’s ambitious INR 18,000 crore PLI scheme for advanced cell chemistry, but 7 year old advanced battery technology startup Log9 is intent on capturing the first mover advantage.It took the first baby step demonstrating its indigenously developed cell manufacturing facility in Bengaluru. With a capacity of just 25 megawatt hour (MWh) and an investment of around $ 25 million (INR 190 crore), it is a drop in the ocean but the ramp up plan is aggressive.

Within one year, Log9 wants to expand its cell manufacturing capacity to 50 MWh while at the same time increasing its battery pack production from 10,000 today to 40,000 units by June and 4 lakh units by March 2023. The investment for this over the year would be another $ 15 million (INR 110 crore). But that’s just a warm up. By 2025, it wants to set up India’s first giga factory, then expanding it 5 fold by 2027 to 5 GWh before expanding it by another 5 fold by the turn of this decade to 25 GWh. The overall investment it would entail would be north of INR 10,000 crore.

“We are too small right now and frankly do not have the money to participate in the PLI scheme. But cell manufacturing is the need of the hour and what is more important is we make cells based on chemistry that is suitable for India,” said Akshay Singhal, founder and CEO, Log9 materials. “Our vision is to be the country’s leading battery solution house. By 2025, we should have attained gigafactory status. Our immediate target is to get to 5 GWh by 2026 or 2027. By the turn of this decade, we will expand this further to 20-25 GWh.”

Lack of lithium ion cell manufacturing is a major hindrance in India’s quest for sustainable electric mobility. Besides high import dependence on countries like China, lack of control on production also gives way to bad quality cells making their way to the market leading to problems like fire hazard in the vehicles. India’s lithium ion battery market was valued at $ 1.66 billion in 2020 and is expected to grow to nearly $ 5 billion by 2027.

“Demand is not a problem, there is enough of it. We are focussed on servicing commercial consumers that use two, three wheelers and small commercial vehicles. That is where our batteries and cells are best suited,” he added. “We have a flexible set up and can produce cells for any type of vehicle or application not just restricted to automotive.”

Log9’s facility is built to produce cells for two types of chemistries–LTO (lithium titanate) and LFP (lithium iron phosphate). It has consciously not chosen NMC (nickel manganese cobalt) which is more energy dense but less stable to high temperatures. LTO is the most stable but packs less energy while LFP is relatively less stable but more dense on energy. There is also a premium for higher stability–LTO costs almost twice as much as NMC.

“You have to strike a balance between stability against high temperatures and energy density. India has a tropical climate with extremes in temperature and NMC is not suited. Which is why we have seen so many fires in recent times,” Singhal said. “LTO offers rapid charging and is best for commercial consumers who cannot afford high charging time. So if you use the vehicle more, the benefit in operating cost will easily cover the higher cost of the technology.”